There is no better way of learning brain structure and function than relating it to a certain behavior. During this project, we were asked to create an image landscape orientation to that connects brain structures, neurotransmitters, and a behavior. For me, I used my episodic memory to explain different brain structures and neurotransmitters related to it.

Episodic Memory: “It takes me back to the same moment”

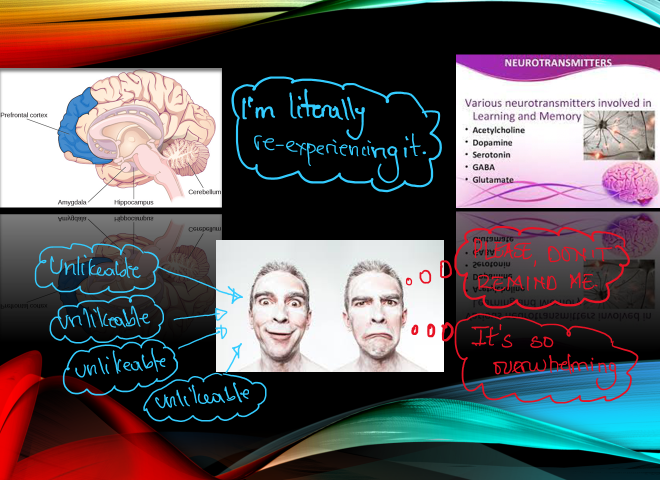

I started having episodic memories followed by mood swings ever since I left high school. This happens often when I am with my friends and one of them mentions jokes around someone they describe as “unlikeable.” This specific word takes me back to my high school freshman year where I faced bullies, and no matter how hard I try to fight my mood shifts, I always find myself swinging from group vibes to sadness and empathy for that person because I know how that description feels. It’s as if I am back to the actual scene. To avoid being the “unlikeable” again, I distance myself from my friends for a while, process the emotions, and come back when I predict the conversation is over. I know this might not be the best way to handle the situation, but for me, the moment is so overwhelming. It’s been three years since I graduated from high school, but this behavior seems to have stuck with me.

Brain Structure and function

Regions of the brain involved in episodic memory are the hippocampus, amygdala, and cerebellum.

Episodic memory, as defined by Endel Tulving, is about recalling the experience and specific details such as when and where the experience was (Ekrem Dere, Bettina M. Pause, Reinhard Peitrowsky). In other words, episodic memory allows us to re-experience the situation as if we were present. The hippocampus, as the center for memory formation, projects information to cortical regions that give memory meaning and connect them to other bits of information enabling one to go back in time. Amygdala works closely with the hippocampus to connect one’s specific emotions with experiences (Kathy Dumper, William Jenkins, Arlene Lacombe, Marilyn Lovett, Marion Perimutter). This means, when a certain word or situation is linked to a special emotion, the amygdala sends signals, almost like it would do during a fight or flight situation, to the hippocampus, giving more emotional sense to the memory retrieved. Lastly, the cerebellum plays an important role in the formation of implicit memories and conditioned responses (Dumper. et al). Considering my situation, since I have had several episodes in which the “unlikeable” word affected my emotions, the same thing will continue to happen because this specific behavior has been recorded in my head as a conditioned response.

Neurotransmitters and Firing neurons

The hippocampus, positioned in the middle of the brain, receives all the sensory information and stores it in the same sorted place. Because of how close those neurons are to each other, the stimulation of one of them affects the others making their connection stronger. In Episodic Memory, video by Serious Science, Neil Burgess mentions that the activation of certain neurons (in this case auditory nerves hearing the “unlikeable” word) leads to reactivation of motor neurons in sensory areas that recreate the experience. Among the other things, one can’t ignore the importance of neurotransmitters in episodic memory. Neurotransmitters, epinephrine, dopamine, glutamate, acetylcholine, and GABA, are the major neurotransmitters known to take part in the process of memory. Although researchers have yet another long journey to make to determine specific roles played by these neurotransmitters, it is indicated that they are linked to specific emotions and experiences.

Epinephrine, together with cortisol, regulate the strength of memory by regulating the release of norepinephrine in the basolateral nucleus of the amygdala. Dopamine signals motivationally important events and regulates the activities of the hippocampus. A study by Gwenn Smith, a professor at Johns Hopkins University school of medicine, suggests that serotonin prevents memory loss. Additionally, the neurotransmitter glutamate helps us to remember stressful events, providing “the functional basis of a phenomenon commonly referred to as flashbulb memory.” (Brain Scan Study) GABA doesn’t directly affect episodic memory, but as an inhibitory neurotransmitter, its absence or lower level of release leads to a “greater long-term potentiation” which strengthens memory and learning. Acetylcholine released in the frontal cortex modulates rhythmic electrical activity that enhances connections between neurons.

To conclude, episodic memory is one of the emotionally connected flashbacks that allows us to re-experience specific moments of our past when a certain trigger is provided.

Reference

1. Ekrem Dere, Bettina M. Pause, Reinhard Peitrowsky. “Emotion and Episodic Memory in Neuropsychiatric Disorders.” Behavioural Brain Research, Elsevier, 12 Mar. 2010, www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0166432810001877?via%3Dihub.

2. Kathy Dumper, William Jenkins, Arlene Lacombe, Marilyn Lovett, Marion Perimutter. “Parts of the Brain Involved in Memory.” PressBooks, https://opentext.wsu.edu/psych105/chapter/8-3-parts-of-the-brain-involved-in-memory/#:~:text=The%20main%20parts%20of%20the,cerebellum%2C%20and%20the%20prefrontal%20cortex.

3. “Episodic Memory.” Performance by Neil Burgess, Serious Science, YouTube, 18 June 2018, www.youtube.com/watch?v=Rk2IFFzhlJM.

“Brain Scan Study Adds to Evidence That Lower Brain Serotonin Levels Are Linked to Dementia – 08/14/2017.” Johns Hopkins Medicine, Based in Baltimore, Maryland, 14 Aug. 2017, www.hopkinsmedicine.org/news/media/releases/brain_scan_study_adds_to_evidence_that_lower_brain_serotonin_levels_are_linked_to_dementia_.